José Manuel Torralba, IMDEA MATERIALS

On November 17, we mark 80 years since U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt commissioned Dr. Vannevar Bush to produce a report well-known to the scientific community but which should also be a priority for policymakers.

The report serves as an extraordinary guide to demonstrate how scientists and scientific knowledge are essential for informed political decision-making. Seems obvious, doesn’t it?

Roosevelt’s request stemmed from his conviction that their imminent victory in World War II was thanks to scientific knowledge.

When Scientists Were Indispensable to Politics

Vannevar Bush, an American engineer and scientist, wielded significant political influence—not just in the development of the atomic bomb.

Beyond the Manhattan Project, Dr. Bush secretly led various scientific endeavours for the government, solving critical issues through the application of science.

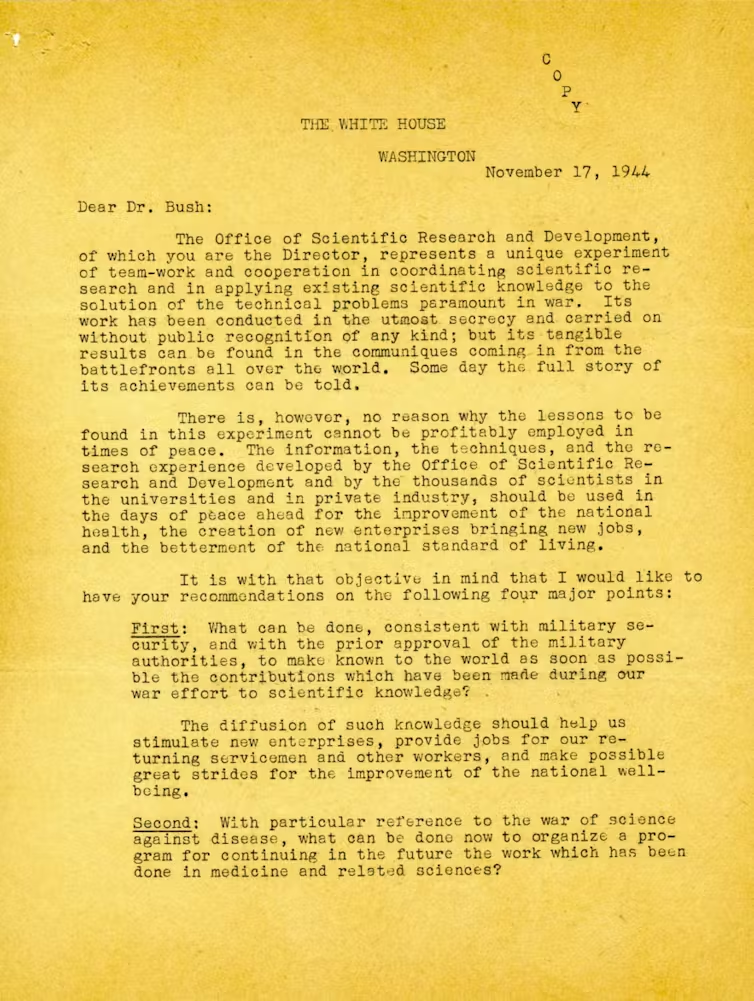

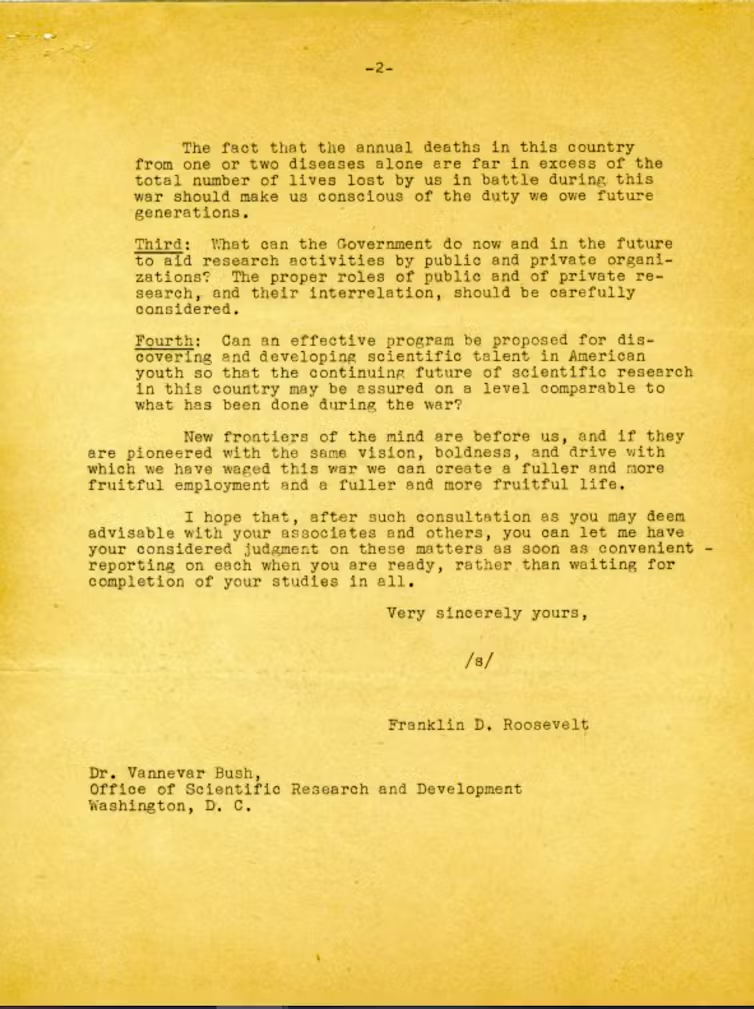

In Roosevelt’s letter to Bush on November 17, 1944, he posed four questions that remain strikingly relevant today. These questions formed the basis of Bush’s subsequent report.

First Question: The Military Use of Science

Roosevelt asked:

“What can be done, consistent with military security and with prior approval of military authorities, to make known to the world the contributions we made to scientific knowledge during our war effort?

The dissemination of this knowledge should help us stimulate new industries, provide jobs for our returning soldiers and other workers, and enable significant progress in national well-being.”

Second Question: The War Against Disease

Roosevelt’s second question addressed public health:

“What can be done now to organize a program to continue scientific work in medicine?

The fact that annual deaths in this country from just one or two diseases far exceed the total lives lost in combat during this war should make us conscious of the obligation we owe to future generations.”

Third Question: Supporting Science

“What can the government do now and in the future to support research activities undertaken by public and private organizations?

The proper role of public and private research, and their interrelation, should be considered very carefully.”

Fourth Question: Nurturing Scientific Talent

Roosevelt also emphasized the need to foster young talent:

“Can an effective program be proposed to identify and develop scientific talent among American youth, so that we can ensure the future continuity of scientific research in this country at a level comparable to that achieved during the war?”

The Bush Report

On July 25, 1945, Vannevar Bush presented a 25-page report titled Science, the Endless Frontier to President Harry Truman (Roosevelt had died prematurely on April 12 that year). The report not only answered Roosevelt’s questions but also laid out a plan for U.S. science policy.

In it, Bush proposed the creation of a state research agency: the National Science Foundation (NSF).

The Bush Report is a true gem. It placed the protection and advancement of scientific knowledge at the heart of governance with a forward-thinking approach that feels modern even today. The goal was to position the U.S. as the world’s leading scientific power.

Securing Funding

Before the Bush Report, the U.S. had won 17 Nobel Prizes in Medicine, Physics, and Chemistry. Afterward, it won 255.

The report made clear the fundamental role of science in national progress, the fight against disease, national security, and public well-being. It emphasized talent as the foundation of knowledge development and acknowledged that achieving these goals requires funding.

Bush advocated for a stable, long-term national science program financed by a dedicated agency composed of individuals with broad interests and a deep understanding of scientific research and education.

Such a body, Bush argued, must respect the autonomy of research institutions in setting their policies, staffing, and methodologies. It should, however, remain accountable to the President and Congress.

“The wisdom with which we apply science in the war against disease, the creation of new industries, and the strengthening of our armed forces will largely determine our future as a nation.”

Promoting Basic Science

Eighty years ago, the report championed the importance of basic science:

“A nation that depends on others for new scientific knowledge will experience slow industrial progress and weakness in its global trade competitiveness, no matter its mechanical skill.”

It also addressed industrial research, emphasizing international cooperation and the development of young talent to ensure continuity in scientific progress.

Despite being an engineer, Bush did not overlook the humanities: “It would be foolish to establish a program where natural sciences and medicine expand at the expense of social sciences, humanities, and other studies essential to national well-being.”

Roosevelt’s Vision Became Reality

Five years after Roosevelt’s death, and thanks to Bush’s persistence, the Truman administration created the NSF, now the world’s leading research agency. The program it developed propelled the U.S. to global leadership in science and economics for decades.

In his letter accompanying the report, Bush’s conclusion remains strikingly applicable today. Science exists—but we lack a Roosevelt.

“The pioneering spirit remains vibrant in our nation. Science offers largely unexplored territory for those equipped with the right tools for the task. The rewards of exploration are immense, both for the nation and the individual. Scientific progress is essential to our national security, health improvements, better jobs, higher living standards, and cultural advancement.”

Roosevelt’s Letter.

José Manuel Torralba, Professor, Carlos III University of Madrid, IMDEA MATERIALES

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original (content in Spanish).